Kinship Is Not Limited to Blood and Can Be Chosen Outside of the Family.

In anthropology, kinship is the spider web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are oft debated. Anthropologist Robin Fob states that "the study of kinship is the written report of what man does with these bones facts of life – mating, gestation, parenthood, socialization, siblingship etc." Man society is unique, he argues, in that we are "working with the aforementioned raw textile equally exists in the creature world, simply [we] can conceptualize and categorize it to serve social ends."[1] These social ends include the socialization of children and the formation of basic economic, political and religious groups.

Kinship can refer both to the patterns of social relationships themselves, or information technology can refer to the report of the patterns of social relationships in i or more man cultures (i.due east. kinship studies). Over its history, anthropology has adult a number of related concepts and terms in the written report of kinship, such as descent, descent group, lineage, affinity/affine, consanguinity/cognate and fictive kinship. Farther, even within these two wide usages of the term, there are dissimilar theoretical approaches.

Broadly, kinship patterns may be considered to include people related past both descent – i.e. social relations during development – and by matrimony. Human kinship relations through marriage are commonly chosen "affinity" in contrast to the relationships that ascend in 1's group of origin, which may be chosen one's descent group. In some cultures, kinship relationships may be considered to extend out to people an individual has economical or political relationships with, or other forms of social connections. Within a civilization, some descent groups may be considered to atomic number 82 dorsum to gods[2] or animal ancestors (totems). This may be conceived of on a more than or less literal ground.

Kinship can besides refer to a principle by which individuals or groups of individuals are organized into social groups, roles, categories and genealogy by means of kinship terminologies. Family relations can be represented concretely (mother, brother, grandfather) or abstractly by degrees of relationship (kinship distance). A relationship may exist relative (eastward.g. a begetter in relation to a child) or reflect an absolute (east.one thousand. the difference between a mother and a childless woman). Degrees of relationship are non identical to heirship or legal succession. Many codes of ethics consider the bond of kinship as creating obligations between the related persons stronger than those betwixt strangers, equally in Confucian filial piety.

In a more general sense, kinship may refer to a similarity or affinity betwixt entities on the basis of some or all of their characteristics that are under focus. This may be due to a shared ontological origin, a shared historical or cultural connexion, or some other perceived shared features that connect the two entities. For example, a person studying the ontological roots of homo languages (etymology) might ask whether there is kinship between the English word seven and the German word sieben. It can exist used in a more diffuse sense as in, for example, the news headline "Madonna feels kinship with vilified Wallis Simpson", to imply a felt similarity or empathy betwixt ii or more than entities.

In biology, "kinship" typically refers to the degree of genetic relatedness or the coefficient of human relationship between private members of a species (east.1000. every bit in kin pick theory). It may also be used in this specific sense when applied to human relationships, in which case its meaning is closer to consanguinity or genealogy.

Basic concepts [edit]

Family types [edit]

Family is a group of people affiliated by consanguinity (past recognized birth), affinity (by marriage), or co-residence/shared consumption (see Nurture kinship). In most societies, information technology is the principal institution for the socialization of children. As the basic unit for raising children, Anthropologists most by and large classify family unit organization as matrifocal (a mother and her children); conjugal (a husband, his married woman, and children; also called nuclear family); avuncular (a blood brother, his sister, and her children); or extended family in which parents and children co-reside with other members of one parent's family.

Withal, producing children is not the just function of the family unit; in societies with a sexual division of labor, spousal relationship, and the resulting relationship between two people, it is necessary for the formation of an economically productive household.[3] [4] [5]

Terminology [edit]

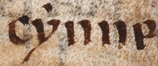

A mention of "cȳnne" (kinsmen) in the Beowulf

Different societies classify kinship relations differently and therefore employ different systems of kinship terminology – for example some languages distinguish between affinal and consanguine uncles, whereas others have only one give-and-take to refer to both a father and his brothers. Kinship terminologies include the terms of address used in different languages or communities for different relatives and the terms of reference used to identify the relationship of these relatives to ego or to each other.

Kin terminologies can be either descriptive or classificatory. When a descriptive terminology is used, a term refers to simply one specific type of relationship, while a classificatory terminology groups many different types of relationships nether one term. For example, the word blood brother in English language-speaking societies indicates a son of 1's same parent; thus, English-speaking societies use the word brother equally a descriptive term referring to this relationship only. In many other classificatory kinship terminologies, in contrast, a person's male first cousin (whether mother's brother's son, mother's sis's son, begetter'due south brother's son, begetter'south sister'due south son) may also exist referred to as brothers.

The major patterns of kinship systems that are known which Lewis Henry Morgan identified through kinship terminology in his 1871 work Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family are:

- Iroquois kinship (also known equally "bifurcate merging")

- Crow kinship (an expansion of bifurcate merging)

- Omaha kinship (also an expansion of bifurcate merging)

- Eskimo kinship (also referred to as "lineal kinship")

- Hawaiian kinship (likewise referred to as the "generational system")

- Sudanese kinship (besides referred to as the "descriptive system")[ commendation needed ]

There is a 7th type of system only identified as distinct later:

- Dravidian kinship (the classical type of classificatory kinship, with bifurcate merging but totally distinct from Iroquois). Almost Australian Ancient kinship is also classificatory.

The half-dozen types (Crow, Eskimo, Hawaiian, Iroquois, Omaha, Sudanese) that are non fully classificatory (Dravidian, Australian) are those identified past Murdock (1949) prior to Lounsbury'southward (1964) rediscovery of the linguistic principles of classificatory kin terms.

Tri-relational Kin-terms [edit]

An illustration of the bi-relational and tri-relational senses of nakurrng in Bininj Gun-Wok.

While normal kin-terms discussed above denote a human relationship betwixt two entities (east.g. the give-and-take 'sister' denotes the human relationship between the speaker or another entity and some other feminine entity who shares the parents of the erstwhile), trirelational kin-terms—besides known as triangular, triadic, ternary, and shared kin-terms—denote a relationship between three distinct entities. These occur ordinarily in Australian Aboriginal languages with the context of Australian Aboriginal kinship.

In Bininj Gun-Wok,[half-dozen] for example, the bi-relational kin-term nakurrng is differentiated from its tri-relational counterpart past the position of the possessive pronoun ke. When nakurrng is anchored to the leaseholder with ke in the second position, it simply means 'blood brother' (which includes a broader set of relations than in English). When the ke is fronted, however, the term nakurrng now incorporates the male speaker as a propositus (P i.e. point of reference for a kin-relation) and encapsulates the entire human relationship as follows:

- The person (R eferent) who is your (P Addressee) maternal uncle and who is my (P Speaker) nephew by virtue of y'all existence my grandchild.

Kin-based Group Terms and Pronouns [edit]

Many Australian languages also accept elaborate systems of referential terms for denoting groups of people based on their human relationship to one another (non merely their relationship to the speaker or an external propositus like 'grandparents'). For example, in Kuuk Thaayorre, a maternal grandfather and his sister are referred to as paanth ngan-ngethe and addressed with the vocative ngethin. [7] In Bardi, a father and his sister are irrmoorrgooloo; a man's married woman and his children are aalamalarr.

In Murrinh-patha, nonsingular pronouns are differentiated non only by the gender makeup of the grouping, but also by the members' interrelation. If the members are in a sibling-like relation, a 3rd pronoun (SIB) will be called distinct from the Masculine (MASC) and Feminine/Neuter (FEM).[8]

Descent [edit]

Descent rules [edit]

In many societies where kinship connections are important, in that location are rules, though they may be expressed or be taken for granted. In that location are iv principal headings that anthropologists use to categorize rules of descent. They are bilateral, unilineal, ambilineal and double descent.[9]

- Bilateral descent or ii-sided descent affiliates an individual more than or less equally with relatives on his male parent's and mother'south sides. A practiced example is the Yakurr of the Crossriver country of Nigeria.

- Unilineal rules affiliates an individual through the descent of i sex activity only, that is, either through males or through females. They are subdivided into 2: patrilineal (male) and matrilineal (female). Most societies are patrilineal. Examples of a matrilineal system of descent are the Nyakyusa of Tanzania and the Nair of Bharat. Many societies that practise a matrilineal arrangement often accept a matrilocal residence but men all the same exercise significant potency.

- Ambilineal (or Cognatic) dominion affiliates an private with kinsmen through the father's or female parent's line. Some people in societies that practice this system affiliate with a group of relatives through their fathers and others through their mothers. The private tin choose which side he wants to affiliate to. The Samoans of the Southward Pacific are an splendid case of an ambilineal gild. The core members of the Samoan descent group can live together in the same compound.

- Double descent (or double unilineal descent) refers to societies in which both the patrilineal and matrilineal descent group are recognized. In these societies an individual affiliates for some purposes with a group of patrilineal kinsmen and for other purposes with a group of matrilineal kinsmen. Individuals in societies that practice this are recognized every bit a part of multiple descent groups, usually at to the lowest degree two. The near widely known case of double descent is the Afikpo of Imo state in Nigeria. Although patrilineage is considered an important method of organisation, the Afikpo considers matrilineal ties to be more than of import.

Descent groups [edit]

A descent group is a social group whose members talk about common ancestry. A unilineal gild is one in which the descent of an individual is reckoned either from the mother's or the father's line of descent. Matrilineal descent is based on relationship to females of the family line. A child would not be recognized with their father'southward family unit in these societies, only would exist seen as a member of their mother'due south family'south line.[10] Simply put, individuals vest to their mother's descent group. Matrilineal descent includes the mother's brother, who in some societies may pass forth inheritance to the sister's children or succession to a sister's son. Conversely, with patrilineal descent, individuals belong to their father'due south descent group. Children are recognized as members of their male parent'southward family unit, and descent is based on relationship to males of the family line.[10] Societies with the Iroquois kinship system, are typically unilineal, while the Iroquois proper are specifically matrilineal.

In a society which reckons descent bilaterally (bilineal), descent is reckoned through both father and mother, without unilineal descent groups. Societies with the Eskimo kinship system, like the Inuit, Yupik, and most Western societies, are typically bilateral. The egoistic kindred group is also typical of bilateral societies. Additionally, the Batek people of Malaysia recognize kinship ties through both parents' family lines, and kinship terms bespeak that neither parent nor their families are of more or less importance than the other.[eleven]

Some societies reckon descent patrilineally for some purposes, and matrilineally for others. This arrangement is sometimes called double descent. For case, certain property and titles may be inherited through the male person line, and others through the female person line.

Societies tin too consider descent to be ambilineal (such every bit Hawaiian kinship) where offspring determine their lineage through the matrilineal line or the patrilineal line.

Lineages, clans, phratries, moieties, and matrimonial sides [edit]

A lineage is a unilineal descent grouping that tin demonstrate their common descent from a known apical ancestor. Unilineal lineages can be matrilineal or patrilineal, depending on whether they are traced through mothers or fathers, respectively. Whether matrilineal or patrilineal descent is considered almost pregnant differs from culture to culture.

A clan is generally a descent group claiming common descent from an apical ancestor. Often, the details of parentage are not important elements of the clan tradition. Not-homo apical ancestors are called totems. Examples of clans are found in Chechen, Chinese, Irish, Japanese, Polish, Scottish, Tlingit, and Somali societies.

A phratry is a descent group composed of two or more clans each of whose upmost ancestors are descended from a farther mutual ancestor.

If a order is divided into exactly 2 descent groups, each is called a moiety, after the French word for half. If the ii halves are each obliged to marry out, and into the other, these are called matrimonial moieties. Houseman and White (1998b, bibliography) take discovered numerous societies where kinship network analysis shows that two halves marry one another, like to matrimonial moieties, except that the two halves—which they phone call matrimonial sides [12]—are neither named nor descent groups, although the egocentric kinship terms may be consistent with the pattern of sidedness, whereas the sidedness is culturally evident but imperfect.[13]

The word deme refers to an endogamous local population that does non have unilineal descent.[14] Thus, a deme is a local endogamous community without internal division into clans.

House societies [edit]

In some societies kinship and political relations are organized around membership in corporately organized dwellings rather than around descent groups or lineages, equally in the "Business firm of Windsor". The concept of a house social club was originally proposed by Claude Lévi-Strauss who called them "sociétés à maison".[fifteen] [16] The concept has been practical to sympathise the system of societies from Mesoamerica and the Moluccas to N Africa and medieval Europe.[17] [18] Lévi-Strauss introduced the concept every bit an culling to 'corporate kinship group' amidst the cognatic kinship groups of the Pacific region. The socially significant groupings inside these societies have variable membership considering kinship is reckoned bilaterally (through both father's and mother's kin) and comes together for only curt periods. Property, genealogy and residence are not the basis for the group's existence.[19]

Union (affinity) [edit]

Marriage is a socially or ritually recognized matrimony or legal contract between spouses that establishes rights and obligations betwixt them, between them and their children, and between them and their in-laws.[xx] The definition of spousal relationship varies according to different cultures, merely it is principally an institution in which interpersonal relationships, usually intimate and sexual, are acknowledged. When defined broadly, marriage is considered a cultural universal. A broad definition of marriage includes those that are monogamous, polygamous, same-sex and temporary.

The act of spousal relationship usually creates normative or legal obligations betwixt the individuals involved, and whatever offspring they may produce. Marriage may consequence, for example, in "a union between a homo and a woman such that children born to the woman are the recognized legitimate offspring of both partners."[21] Edmund Leach argued that no one definition of spousal relationship practical to all cultures, simply offered a list of ten rights often associated with marriage, including sexual monopoly and rights with respect to children (with specific rights differing across cultures).[22]

There is wide cross-cultural variation in the social rules governing the choice of a partner for marriage. In many societies, the choice of partner is limited to suitable persons from specific social groups. In some societies the rule is that a partner is selected from an individual'due south own social grouping – endogamy, this is the case in many class and caste based societies. But in other societies a partner must be chosen from a different group than one'south own – exogamy, this is the instance in many societies practicing totemic religion where society is divided into several exogamous totemic clans, such equally near Aboriginal Australian societies. Marriages betwixt parents and children, or betwixt full siblings, with few exceptions,[23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] take been considered incest and forbidden. However, marriages betwixt more than afar relatives have been much more common, with ane estimate being that 80% of all marriages in history have been betwixt second cousins or closer.[xxx]

Brotherhood (marital exchange systems) [edit]

Systemic forms of preferential marriage may have wider social implications in terms of economic and political organization. In a broad array of lineage-based societies with a classificatory kinship system, potential spouses are sought from a specific class of relatives equally determined past a prescriptive marriage rule. Insofar as regular marriages following prescriptive rules occur, lineages are linked together in stock-still relationships; these ties between lineages may form political alliances in kinship dominated societies.[31] French structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss developed the alliance theory to account for the "simple" kinship structures created by the limited number of prescriptive spousal relationship rules possible.[32]

Claude Lévi-Strauss argued in The Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949), that the incest taboo necessitated the exchange of women betwixt kinship groups. Levi-Strauss thus shifted the emphasis from descent groups to the stable structures or relations between groups that preferential and prescriptive marriage rules created.[33]

History [edit]

One of the foundational works in the anthropological study of kinship was Morgan'due south Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family unit (1871). As is the case with other social sciences, Anthropology and kinship studies emerged at a fourth dimension when the understanding of the Man species' comparative place in the world was somewhat different from today'south. Evidence that life in stable social groups is non just a characteristic of humans, but besides of many other primates, was yet to emerge and society was considered to exist a uniquely human affair. As a issue, early kinship theorists saw an credible need to explicate non only the details of how human social groups are constructed, their patterns, meanings and obligations, merely also why they are synthetic at all. The why explanations thus typically presented the fact of life in social groups (which appeared to be unique to humans) equally being largely a result of human being ideas and values.

Morgan's early on influence [edit]

Morgan's explanation for why humans live in groups was largely based on the notion that all humans have an inherent natural valuation of genealogical ties (an unexamined assumption that would remain at the heart of kinship studies for another century, see beneath), and therefore also an inherent want to construct social groups effectually these ties. Nevertheless, Morgan establish that members of a society who are not close genealogical relatives may yet use what he chosen kinship terms (which he considered to be originally based on genealogical ties). This fact was already evident in his utilize of the term affinity within his concept of the system of kinship. The most lasting of Morgan'southward contributions was his discovery of the difference between descriptive and classificatory kinship terms, which situated broad kinship classes on the basis of imputing abstract social patterns of relationships having footling or no overall relation to genetic closeness only instead knowledge almost kinship, social distinctions as they affect linguistic usages in kinship terminology, and strongly chronicle, if only by approximation, to patterns of marriage.[thirteen]

Kinship networks and social process[34] [edit]

A more flexible view of kinship was formulated in British social anthropology. Among the attempts to break out of universalizing assumptions and theories virtually kinship, Radcliffe-Brown (1922, The Andaman Islands; 1930, The social organisation of Australian tribes) was the kickoff to assert that kinship relations are all-time idea of equally concrete networks of relationships among individuals. He and then described these relationships, however, equally typified by interlocking interpersonal roles. Malinowski (1922, Argonauts of the Western Pacific) described patterns of events with physical individuals as participants stressing the relative stability of institutions and communities, just without insisting on abstract systems or models of kinship. Gluckman (1955, The judicial process among the Barotse of Northern Rhodesia) balanced the accent on stability of institutions against processes of change and disharmonize, inferred through detailed analysis of instances of social interaction to infer rules and assumptions. John Barnes, Victor Turner, and others, affiliated with Gluckman's Manchester school of anthropology, described patterns of bodily network relations in communities and fluid situations in urban or migratory context, equally with the work of J. Clyde Mitchell (1965, Social Networks in Urban Situations). Yet, all these approaches clung to a view of stable functionalism, with kinship as one of the primal stable institutions.

"Kinship system" as systemic pattern [edit]

The concept of "arrangement of kinship" tended to boss anthropological studies of kinship in the early 20th century. Kinship systems equally defined in anthropological texts and ethnographies were seen as constituted by patterns of beliefs and attitudes in relation to the differences in terminology, listed to a higher place, for referring to relationships besides every bit for addressing others. Many anthropologists went so far as to run into, in these patterns of kinship, potent relations between kinship categories and patterns of marriage, including forms of wedlock, restrictions on spousal relationship, and cultural concepts of the boundaries of incest. A great deal of inference was necessarily involved in such constructions as to "systems" of kinship, and attempts to construct systemic patterns and reconstruct kinship evolutionary histories on these bases were largely invalidated in subsequently work. Nonetheless, anthropologist Dwight Read afterward argued that the way in which kinship categories are defined by private researchers are substantially inconsistent.[35] This not only occurs when working within a systemic cultural model that tin exist elicited in fieldwork, just also when allowing considerable individual variability in details, such as when they are recorded through relative products.[36]

Alien theories of the mid 20th century[37] [edit]

In trying to resolve the problems of dubious inferences about kinship "systems", George P. Murdock (1949, Social Structure) compiled kinship data to examination a theory about universals in human being kinship in the manner that terminologies were influenced by the behavioral similarities or social differences among pairs of kin, proceeding on the view that the psychological ordering of kinship systems radiates out from ego and the nuclear family to different forms of extended family. Lévi-Strauss (1949, Les Structures Elementaires), on the other mitt, too looked for global patterns to kinship, but viewed the "unproblematic" forms of kinship as lying in the ways that families were connected past marriage in different fundamental forms resembling those of modes of exchange: symmetric and directly, reciprocal delay, or generalized exchange.

Recognition of fluidity in kinship meanings and relations [edit]

Building on Lévi-Strauss's (1949) notions of kinship as caught up with the fluid languages of commutation, Edmund Leach (1961, Pul Eliya) argued that kinship was a flexible idiom that had something of the grammar of a language, both in the uses of terms for kin but as well in the fluidities of language, meaning, and networks. His field studies criticized the ideas of structural-functional stability of kinship groups as corporations with charters that lasted long beyond the lifetimes of individuals, which had been the orthodoxy of British Social Anthropology. This sparked debates over whether kinship could be resolved into specific organized sets of rules and components of significant, or whether kinship meanings were more fluid, symbolic, and independent of grounding in supposedly determinate relations amidst individuals or groups, such as those of descent or prescriptions for marriage.

From the 1950s onwards, reports on kinship patterns in the New Guinea Highlands added some momentum to what had until and then been only occasional fleeting suggestions that living together (co-residence) might underlie social bonding, and somewhen contributed to the full general shift abroad from a genealogical approach (see below section). For example, on the basis of his observations, Barnes suggested:

[C]learly, genealogical connection of some sort is one benchmark for membership of many social groups. Simply information technology may not be the only benchmark; nascence, or residence, or a parent's former residence, or utilization of garden land, or participation in exchange and feasting activities or in house-building or raiding, may be other relevant criteria for grouping membership."(Barnes 1962,6)[38]

Similarly, Langness' ethnography of the Bena Bena also emphasized the primacy of residence patterns in 'creating' kinship ties:

The sheer fact of residence in a Bena Bena grouping can and does determine kinship. People practice not necessarily reside where they practise because they are kinsmen: rather they become kinsmen considering they reside in that location." (Langness 1964, 172 emphasis in original)[39]

In 1972 David K. Schneider raised[40] deep issues with the notion that human being social bonds and 'kinship' was a natural category built upon genealogical ties and made a fuller argument in his 1984 book A critique of the report of Kinship [41] which had a major influence on the subsequent study of kinship.

Schneider's critique of genealogical concepts [edit]

Before the questions raised within anthropology about the study of 'kinship' past David Chiliad. Schneider[41] and others from the 1960s onwards, anthropology itself had paid very lilliputian attending to the notion that kinship bonds were anything other than connected to consanguineal (or genealogical) relatedness (or its local cultural conceptions). Schneider'southward 1968 study[42] of the symbolic meanings surrounding ideas of kinship in American Culture found that Americans ascribe a special significance to 'claret ties' likewise every bit related symbols like the naturalness of union and raising children within this civilization. In later work (1972 and 1984) Schneider argued that unexamined genealogical notions of kinship had been embedded in anthropology since Morgan's early work[43] considering American anthropologists (and anthropologists in western Europe) had made the mistake of assuming these particular cultural values of 'claret is thicker than water', common in their ain societies, were 'natural' and universal for all human cultures (i.east. a course of ethnocentrism). He concluded that, due to these unexamined assumptions, the whole enterprise of 'kinship' in anthropology may have been built on faulty foundations. His 1984 volume A Critique of The Written report of Kinship gave his fullest business relationship of this critique.

Certainly for Morgan (1870:10) the actual bonds of blood relationship had a force and vitality of their own quite apart from any social overlay which they may also have caused, and it is this biological human relationship itself which accounts for what Radcliffe-Brown called "the source of social cohesion". (Schneider 1984, 49)

Schneider himself emphasised a distinction between the notion of a social relationship as intrinsically given and inalienable (from nativity), and a social relationship every bit created, constituted and maintained past a process of interaction, or doing (Schneider 1984, 165). Schneider used the example of the citamangen / fak human relationship in Yap society, that his own early enquiry had previously glossed over as a father / son human relationship, to illustrate the problem;

The crucial point is this: in the human relationship between citamangen and fak the stress in the definition of the relationship is more on doing than on being. That is, it is more what the citamangen does for fak and what fak does for citamangen that makes or constitutes the relationship. This is demonstrated, start, in the ability to terminate absolutely the human relationship where at that place is a failure in the doing, when the fak fails to exercise what he is supposed to do; and second, in the reversal of terms so that the old, dependent human becomes fak, to the swain, tam. The European and the anthropological notion of consanguinity, of claret relationship and descent, rest on precisely the reverse kind of value. It rests more than on the land of beingness... on the biogenetic relationship which is represented by one or some other variant of the symbol of 'blood' (consanguinity), or on 'birth', on qualities rather than on performance. We have tried to impose this definition of a kind of relation on all peoples, insisting that kinship consists in relations of consanguinity and that kinship as consanguinity is a universal condition.(Schneider 1984, 72)

Schneider preferred to focus on these often ignored processes of "performance, forms of doing, diverse codes for behave, different roles" (p. 72) as the about of import constituents of kinship. His critique quickly prompted a new generation of anthropologists to reconsider how they conceptualized, observed and described social relationships ('kinship') in the cultures they studied.

Post-Schneider [edit]

Schneider's critique is widely best-selling[44] [45] [46] to accept marked a turning point in anthropology's study of social relationships and interactions. Some anthropologists moved forward with kinship studies by teasing autonomously biological and social aspects, prompted by Schneider's question;

The question of whether kinship is a privileged organization and if so, why, remains without a satisfactory answer. If it is privileged considering of its relationship to the functional prerequisites imposed by the nature of physical kinship, this remains to be spelled out in fifty-fifty the most elementary detail. (Schneider 1984, 163)

Schneider as well dismissed the sociobiological business relationship of biological influences, maintaining that these did not fit the ethnographic evidence (see more below). Janet Carsten employed her studies with the Malays[47] to reassess kinship. She uses the idea of relatedness to movement abroad from a pre-constructed analytic opposition between the biological and the social. Carsten argued that relatedness should be described in terms of ethnic statements and practices, some of which autumn exterior what anthropologists have conventionally understood as kinship;

Ideas about relatedness in Langkawi evidence how culturally specific is the separation of the 'social' from the 'biological' and the latter to sexual reproduction. In Langkawi relatedness is derived both from acts of procreation and from living and eating together. Information technology makes little sense in ethnic terms to label some of these activities equally social and others every bit biological. (Carsten 1995, 236)

Philip Thomas' work with the Temanambondro of Madagascar highlights that nurturing processes are considered to be the 'basis' for kinship ties in this culture, all the same genealogical connections;

Notwithstanding just every bit fathers are not simply made by nativity, neither are mothers, and although mothers are not made past "custom" they, like fathers, can make themselves through another type of performatively constituted relation, the giving of "nurture". Relations of ancestry are specially important in contexts of ritual, inheritance and the defining of marriageability and incest; they are in effect the "structuring structures" (Bourdieu 1977) of social reproduction and intergenerational continuity. Father, mother and children are, still, as well performatively related through the giving and receiving of "nurture" (fitezana). Like beginnings, relations of "nurture" do not always coincide with relations by birth; but dissimilar ancestry, "nurture" is a largely ungendered relation, constituted in contexts of everyday applied existence, in the intimate, familial and familiar earth of the household, and in ongoing relations of piece of work and consumption, of feeding and farming. (Thomas 1999, 37)[48]

Like ethnographic accounts have emerged from a diverseness of cultures since Schneider'due south intervention. The concept of nurture kinship highlights the extent to which kinship relationships may be brought into being through the performance of various acts of nurture between individuals. Additionally the concept highlights ethnographic findings that, in a broad swath of man societies, people understand, conceptualize and symbolize their relationships predominantly in terms of giving, receiving and sharing nurture. These approaches were somewhat forerun by Malinowski, in his ethnographic study of sexual behaviour on the Trobriand Islands which noted that the Trobrianders did not believe pregnancy to be the result of sexual intercourse between the man and the woman, and they denied that there was any physiological relationship between begetter and kid.[49] Yet, while paternity was unknown in the "full biological sense", for a woman to have a child without having a husband was considered socially undesirable. Fatherhood was therefore recognised every bit a social and nurturing role; the woman's husband is the "human whose office and duty information technology is to take the child in his artillery and to help her in nursing and bringing information technology up";[50] "Thus, though the natives are ignorant of whatsoever physiological need for a male person in the constitution of the family, they regard him every bit indispensable socially".[51]

Biology, psychology and kinship [edit]

Similar Schneider, other anthropologists of kinship take largely rejected sociobiological accounts of homo social patterns as being both reductionistic and likewise empirically incompatible with ethnographic data on human kinship. Notably, Marshall Sahlins strongly critiqued the sociobiological approach through reviews of ethnographies in his 1976 The Utilise and Abuse of Biology [52] noting that for humans "the categories of 'near' and 'afar' [kin] vary independently of consanguinal distance and that these categories organize bodily social practice" (p. 112).

Independently from anthropology, biologists studying organisms' social behaviours and relationships have been interested to understand under what conditions significant social behaviors can evolve to become a typical feature of a species (see inclusive fitness theory). Because circuitous social relationships and cohesive social groups are common non only to humans, but also to most primates, biologists maintain that these biological theories of sociality should in principle be by and large applicable. The more challenging question arises equally to how such ideas can be applied to the human species whilst fully taking account of the all-encompassing ethnographic evidence that has emerged from anthropological inquiry on kinship patterns.

Early developments of biological inclusive fitness theory and the derivative field of Sociobiology, encouraged some sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists to approach human kinship with the supposition that inclusive fitness theory predicts that kinship relations in humans are indeed expected to depend on genetic relatedness, which they readily connected with the genealogy approach of early anthropologists such as Morgan (see to a higher place sections). However, this is the position that Schneider, Sahlins and other anthropologists explicitly reject.

Nonreductive biological science and nurture kinship [edit]

In agreement with Schneider, Holland argued[53] that an accurate account of biological theory and evidence supports the view that social bonds (and kinship) are indeed mediated by a shared social environment and processes of frequent interaction, care and nurture, rather than past genealogical relationships per se (even if genealogical relationships frequently correlate with such processes). In his 2012 volume Social bonding and nurture kinship The netherlands argues that sociobiologists and subsequently evolutionary psychologists misrepresent biological theory, mistakenly believing that inclusive fitness theory predicts that genetic relatedness per se is the condition that mediates social bonding and social cooperation in organisms. Holland points out that the biological theory (see inclusive fitness) only specifies that a statistical relationship between social behaviors and genealogical relatedness is a criterion for the evolution of social behaviors. The theory'south originator, Due west.D.Hamilton considered that organisms' social behaviours were probable to be mediated past full general conditions that typically correlate with genetic relatedness, just are not probable to be mediated past genetic relatedness per se [54] (see Human inclusive fitness and Kin recognition). Kingdom of the netherlands reviews fieldwork from social mammals and primates to prove that social bonding and cooperation in these species is indeed mediated through processes of shared living context, familiarity and attachments, not by genetic relatedness per se. Holland thus argues that both the biological theory and the biological evidence is nondeterministic and nonreductive, and that biology as a theoretical and empirical endeavor (as opposed to 'biology' every bit a cultural-symbolic nexus every bit outlined in Schneider's 1968 book) really supports the nurture kinship perspective of cultural anthropologists working post-Schneider (run into above sections). Holland argues that, whilst there is nonreductive compatibility around human kinship between anthropology, biological science and psychology, for a total account of kinship in any particular human civilization, ethnographic methods, including accounts of the people themselves, the assay of historical contingencies, symbolic systems, economic and other cultural influences, remain centrally of import.

Holland's position is widely supported past both cultural anthropologists and biologists every bit an approach which, according to Robin Fox, "gets to the center of the thing concerning the contentious relationship between kinship categories, genetic relatedness and the prediction of beliefs".[55]

Evolutionary psychology [edit]

The other approach, that of Evolutionary psychology, continues to accept the view that genetic relatedness (or genealogy) is primal to agreement human kinship patterns. In contrast to Sahlin'due south position (above), Daly and Wilson argue that "the categories of 'near' and 'distant' do not 'vary independently of consanguinal distance', not in any guild on earth." (Daly et al. 1997,[56] p282). A current view is that humans have an inborn but culturally affected organization for detecting certain forms of genetic relatedness. Ane of import cistron for sibling detection, especially relevant for older siblings, is that if an infant and one's mother are seen to care for the baby, then the infant and oneself are assumed to be related. Another factor, particularly important for younger siblings who cannot employ the kickoff method, is that persons who grew up together see 1 another as related. Yet some other may be genetic detection based on the major histocompatibility complex (Come across Major Histocompatibility Circuitous and Sexual Selection). This kinship detection organization in turn affects other genetic predispositions such as the incest taboo and a tendency for altruism towards relatives.[57]

One issue within this arroyo is why many societies organize co-ordinate to descent (see below) and not exclusively according to kinship. An explanation is that kinship does not course clear boundaries and is centered differently for each individual. In contrast, descent groups usually practise form clear boundaries and provide an easy way to create cooperative groups of various sizes.[58]

According to an evolutionary psychology hypothesis that assumes that descent systems are optimized to assure loftier genetic probability of relatedness between lineage members, males should adopt a patrilineal system if paternal certainty is high; males should prefer a matrilineal system if paternal certainty is low. Some research supports this association with one study finding no patrilineal society with low paternity confidence and no matrilineal society with loftier paternal certainty. Another association is that pastoral societies are relatively more than often patrilineal compared to horticultural societies. This may exist because wealth in pastoral societies in the class of mobile cattle can easily exist used to pay bride cost which favor concentrating resources on sons then they can marry.[58]

The evolutionary psychology business relationship of biological science continues to be rejected by most cultural anthropologists.

Extensions of the kinship metaphor [edit]

Fictive kinship [edit]

Detailed terms for parentage [edit]

Every bit social and biological concepts of parenthood are not necessarily coterminous, the terms "pater" and "genitor" have been used in anthropology to distinguish between the human being who is socially recognised equally father (pater) and the man who is believed to exist the physiological parent (genitor); similarly the terms "mater" and "genitrix" have been used to distinguish between the woman socially recognised every bit mother (mater) and the adult female believed to be the physiological parent (genitrix).[59] Such a distinction is useful when the individual who is considered the legal parent of the child is not the private who is believed to be the child's biological parent. For example, in his ethnography of the Nuer, Evans-Pritchard notes that if a widow, post-obit the death of her hubby, chooses to live with a lover exterior of her deceased husband'south kin group, that lover is only considered genitor of any subsequent children the widow has, and her deceased husband continues to be considered the pater. As a result, the lover has no legal control over the children, who may be taken away from him by the kin of the pater when they choose.[60] The terms "pater" and "genitor" have also been used to help describe the relationship between children and their parents in the context of divorce in Britain. Following the divorce and remarriage of their parents, children find themselves using the term "female parent" or "begetter" in relation to more one private, and the pater or mater who is legally responsible for the kid's care, and whose family proper name the kid uses, may not be the genitor or genitrix of the child, with whom a separate parent-child relationship may be maintained through arrangements such as visitation rights or articulation custody.[61]

Information technology is important to note that the terms "genitor" or "genetrix" exercise not necessarily imply actual biological relationships based on consanguinity, but rather refer to the socially held belief that the private is physically related to the child, derived from culturally held ideas about how biology works. Then, for example, the Ifugao may believe that an illegitimate child might take more than than ane physical father, and so nominate more than than 1 genitor.[62] J.A. Barnes therefore argued that it was necessary to make a farther distinction between genitor and genitrix (the supposed biological mother and father of the child), and the bodily genetic father and mother of the child making them share their genes or genetics .

Limerick of relations [edit]

The report of kinship may be bathetic to binary relations between people. For example, if x is the parent of y, the relation may be symbolized as xPy. The antipodal relation, that y is the kid of x, is written yP T ten. Suppose that z is another child of x: zP T 10. And so y is a sibling of z every bit they share the parent 10: zP T xPy → zP T Py . Here the relation of siblings is expressed as the composition P T P of the parent relation with its inverse.

The relation of grandparent is the limerick of the parent relation with itself: G = PP . The relation of uncle is the composition of parent with blood brother, while the relation of aunt composes parent with sister. Suppose x is the grandparent of y: xGy. And so y and z are cousins if yG T xGz.

The symbols applied here to express kinship are used more mostly in algebraic logic to develop a calculus of relations with sets other than human beings.

Appendix [edit]

Degrees [edit]

| Kinship | Caste of relationship | Genetic overlap |

|---|---|---|

| Inbred Strain | not applicable | 99% |

| Identical twins | first-degree | 100%[63] |

| Full sibling | first-degree | 50% (2−1) |

| Parent[64] | beginning-degree | 50% (2−1) |

| Child | showtime-caste | 50% (2−ane) |

| Half-sibling | second-caste | 25% (two−2) |

| 3/iv siblings or sibling-cousin | 2d-degree | 37.v% (3⋅2−iii) |

| Grandparent | second-degree | 25% (2−2) |

| Grandchild | second-degree | 25% (ii−2) |

| Aunt/uncle | second-degree | 25% (ii−two) |

| Niece/nephew | second-degree | 25% (2−2) |

| Half-aunt/half-uncle | 3rd-caste | 12.5% (2−3) |

| Half-niece/half-nephew | third-degree | 12.five% (2−3) |

| Cracking grandparent | third-degree | 12.5% (2−3) |

| Bang-up grandchild | third-degree | 12.v% (2−three) |

| Great aunt/not bad uncle | third-degree | 12.five% (2−3) |

| Great niece/bully nephew | tertiary-degree | 12.five% (ii−3) |

| First cousin | third-degree | 12.v% (2−three) |

| Double first cousin | 2d-degree | 25% (2−2) |

| One-half-kickoff cousin | quaternary-degree | 6.25% (ii−4) |

| First cousin in one case removed | fourth-degree | 6.25% (2−4) |

| 2d cousin | 5th-degree | 3.125% (2−5) |

| Double second cousin | fourth-degree | 6.25% (2−four) |

| Triple second cousin | fourth-degree | 9.375% (iii⋅2−five) |

| Quadruple second cousin | 3rd-degree | 12.5% (ii−3) |

| Third cousin | 7th-degree | 0.781% (2−vii) |

| Fourth cousin | ninth-degree | 0.xx% (2−9)[65] |

See also [edit]

- Ancestry

- Kin choice

- Kinism

- Kinship analysis

- Kinship terminology

- Australian Aboriginal kinship

- Bride price

- Bride service

- Chinese kinship

- Cinderella effect

- Association

- Consanguinity

- Darwinian anthropology

- Dynasty

- Ethnicity

- Family

- Family history

- Fictive kinship

- Genealogy

- Genetic genealogy

- Godparent

- Heredity

- Inheritance

- Interpersonal relationships

- Irish Kinship

- Lineage (anthropology)

- Nurture kinship

- Serbo-Croatian kinship

- Tribe

- Firm society

References [edit]

- ^ Fox, Robin (1967). Kinship and Union. Harmondsworth, UK: Pelican Books. p. 30.

- ^ On Kinship and Gods in Ancient Arab republic of egypt: An Interview with Marcelo Campagno Damqatum 2 (2007)

- ^ Wolf, Eric. 1982 Europe and the People Without History. Berkeley: University of California Press. 92

- ^ Harner, Michael 1975 "Scarcity, the Factors of Product, and Social Evolution," in Population. Ecology, and Social Evolution, Steven Polgar, ed. Mouton Publishers: the Hague.

- ^ Rivière, Peter 1987 "Of Women, Men, and Manioc", Etnologiska Studien (38).

- ^ Skin, kin and clan : the dynamics of social categories in Indigenous Commonwealth of australia. McConvell, Patrick,, Kelly, Piers,, Lacrampe, Sébastien,, Australian National Academy Press. Acton, A.C.T. Apr 2018. ISBN978-1-76046-164-v. OCLC 1031832109.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Gaby, Alice Rose. 2006. A Grammer of Kuuk Thaayorre. The University of Melbourne Ph.D.

- ^ Walsh, Michael James. 1976. The Muɹinypata Language of Northern Australia. The Australian National University.

- ^ Oke Wale, An Introduction to Social Anthropology Second Edition, Part 2, Kinship.

- ^ a b Monaghan, John; But, Peter (2000). Social & Cultural Anthropology: A Very Short Introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 86–88. ISBN978-0-nineteen-285346-2.

- ^ Endicott, Kirk M.; Endicott, Karen Fifty. (2008). The Headman Was a Woman: The Gender Egalitarian Batek of Malaysia. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc. pp. 26–27. ISBN978-1-57766-526-7.

- ^ Houseman and White 1998b harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFHouseman_and_White1998b (help)

- ^ a b Houseman & White 1998a harvnb mistake: no target: CITEREFHousemanWhite1998a (aid)

- ^ Spud, Michael Dean. "Kinship Glossary". Retrieved 2009-03-thirteen .

- ^ Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1982). The Mode of the Mask. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- ^ Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1987. Anthropology and Myth: Lectures, 1951–1982. R. Willis, trans. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- ^ Joyce, Rosemary A. & Susan D. Gillespie (eds.). 2000. Beyond Kinship: Social and Material Reproduction in Firm Societies. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ Carsten, Janet & Stephen Hugh-Jones (eds.) About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Across. Cambridge University Press, May 4, 1995

- ^ Errington, Shelly (1989). Meaning and Ability in a Southeast Asian Realm. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Printing. p. 236.

- ^ Haviland, William A.; Prins, Harald E. L.; McBride, Bunny; Walrath, Dana (2011). Cultural Anthropology: The Human Challenge (13th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN978-0-495-81178-7.

- ^ Notes and Queries on Anthropology. Royal Anthropological Institute. 1951. p. 110.

- ^ Leach, Edmund (December 1955). "Polyandry, Inheritance and the Definition of Marriage". Man. 55 (12): 182–186. doi:10.2307/2795331. JSTOR 2795331.

- ^ Strong, Anise (2006). "Incest Laws and Absent-minded Taboos in Roman Arab republic of egypt". Ancient History Message. 20.

- ^ Lewis, N. (1983). Life in Egypt under Roman Dominion . Clarendon Press. ISBN978-0-19-814848-seven.

- ^ Frier, Bruce W.; Bagnall, Roger South. (1994). The Demography of Roman Arab republic of egypt. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-46123-8.

- ^ Shaw, B. D. (1992). "Explaining Incest: Brother-Sister Marriage in Graeco-Roman Arab republic of egypt". Man. New Series. 27 (2): 267–299. doi:10.2307/2804054. JSTOR 2804054.

- ^ Hopkins, Keith (1980). "Blood brother-Sister Marriage in Roman Egypt". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 22 (3): 303–354. doi:10.1017/S0010417500009385.

- ^ remijsen, sofie. "Incest or Adoption? Blood brother-Sis Marriage in Roman Egypt Revisited" (PDF).

- ^ Scheidel, W (1997). "Brother-sister marriage in Roman Egypt" (PDF). Journal of Biosocial Scientific discipline. 29 (3): 361–71. doi:10.1017/s0021932097003611. PMID 9881142.

- ^ Conniff, Richard (1 August 2003). "Richard Conniff. "Go Ahead, Buss Your Cousin."". Discovermagazine.com.

- ^ Radcliffe-Brownish, A.R., Daryll Forde (1950). African Systems of Kinship and Matrimony. London: KPI Express.

- ^ Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1963). Structural Anthropology . New York: Basic Books.

- ^ Kuper, Adam (2005). The Reinvention of Primitive Society: Transformations of a myth. London: Routledge. pp. 179–90.

- ^ White & Johansen 2005, Chapters iii and four

- ^ Read 2001

- ^ Wallace & Atkins 1960

- ^ White & Johansen 2005, Chapter 4

- ^ Barnes, J.A. (1962). "African models in the New Republic of guinea Highlands". Human being. 62: 5–9. doi:10.2307/2795819. JSTOR 2795819.

- ^ Langness, L.Fifty. (1964). "Some problems in the conceptualization of Highlands social structures". American Anthropologist. 66 (4 pt 2): 162–182. JSTOR 668436.

- ^ Schneider, D. 1972. What is Kinship all About. In Kinship Studies in the Morgan Centennial Yr, edited past P. Reining. Washington: Anthropological Society of Washington.

- ^ a b Schneider, D. 1984. A critique of the written report of kinship. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- ^ Schneider, D. 1968. American kinship: a cultural account, Anthropology of modern societies series. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

- ^ Morgan, Lewis Henry. 1870. Systems of consanguity and affinity of the homo family. Vol. 17, Smithsonian Contributions to Noesis. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Collier, Jane Fishburne; Yanagisako, Sylvia Junko (1987). Gender and kinship: Essays toward a unified analysis. Stanford University Press.

- ^ Carsten, Janet (2000). Cultures of relatedness: New approaches to the study of kinship. Cambridge University Printing.

- ^ Strathern, Marilyn. After nature: English kinship in the late twentieth century. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Carsten, Janet (1995). "The substance of kinship and the middle of the hearth". American Ethnologist. 22 (2): 223–241. doi:ten.1525/ae.1995.22.two.02a00010. S2CID 145716250.

- ^ Thomas, Philip. (1999) No substance, no kinship? Procreation, Performativity and Temanambondro parent/child relations. In Conceiving persons: ethnographies of procreation, fertility, and growth edited by P. Loizos and P. Heady. New Brunswick, NJ: Athlone Printing.

- ^ Malinowski 1929, pp. 179–186

- ^ Malinowski 1929, p. 195

- ^ Malinowski 1929, p. 202

- ^ Sahlins, Marshal (1976). The Use and Corruption of Biology .

- ^ The netherlands, Maximilian. (2012) Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship: Compatibility between Cultural and Biological Approaches. North Charleston: Createspace Printing.

- ^ Hamilton, West.D. 1987. Discriminating nepotism: expectable, mutual and disregarded. In Kin recognition in animals, edited by D. J. C. Fletcher and C. D. Michener. New York: Wiley.

- ^ Holland, Maximilian (26 Oct 2012). Robin Pull a fast one on comment (book cover). ISBN978-1480182004.

- ^ Daly, Martin; Salmon, Catherine; Wilson, Margo (1997). Kinship: the conceptual hole in psychological studies of social cognition and close relationships. Erlbaum.

- ^ Lieberman, D.; Tooby, J.; Cosmides, L. (2007). "The architecture of human kin detection". Nature. 445 (7129): 727–731. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..727L. doi:ten.1038/nature05510. PMC3581061. PMID 17301784.

- ^ a b The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, Edited by Robin Dunbar and Louise Barret, Oxford University Press, 2007, Chapter 31 Kinship and descent by Lee Conk and Drew Gerkey

- ^ Fox 1977, p. 34

- ^ Evans-Pritchard 1951, p. 116

- ^ Simpson 1994, pp. 831–851

- ^ Barnes 1961, pp. 296–299

- ^ By replacement in the definition of the notion of "generation" past meiosis". Since identical twins are not separated by meiosis, there are no "generations" betwixt them, hence n=0 and r=1. See genetic-genealogy.co.uk.

- ^ "Kin Selection". Benjamin/Cummings. Retrieved 2007-11-25 .

- ^ This degree of relationship is usually indistinguishable from the human relationship to a random private within the aforementioned population (tribe, country, ethnic group).

Bibliography [edit]

- Barnes, J. A. (1961). "Physical and Social Kinship". Philosophy of Science. 28 (3): 296–299. doi:10.1086/287811. S2CID 122178099.

- Boon, James A.; Schneider, David M. (October 1974). "Kinship vis-a-vis Myth Contrasts in Levi-Strauss' Approaches to Cross-Cultural Comparison". American Anthropologist. 76 (4): 799–817. doi:10.1525/aa.1974.76.4.02a00050.

- Bowlby, John (1982). Attachment. Vol. ane (2nd ed.). London: Hogarth.

- Evans-Pritchard, Eastward. E. (1951). Kinship and Marriage amidst the Nuer. Oxford: Clarendon Printing.

- Trick, Robin (1977). Kinship and Marriage: An Anthropological Perspective. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Kingdom of the netherlands, Maximilian (2012). Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship: Compatibility Between Cultural and Biological Approaches. Createspace Press.

- Houseman, Michael; White, Douglas R. (1998). "Network mediation of commutation structures: Ambilateral sidedness and belongings flows in Pul Eliya" (PDF). In Schweizer, Thomas; White, Douglas R. (eds.). Kinship, Networks and Exchange. Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2019.

- Houseman, Michael; White, Douglas R. (1998). "Taking Sides: Marriage Networks and Dravidian Kinship in Lowland South America" (PDF). In Godelier, Maurice; Trautmann, Thomas; F.Tjon Sie Fat. (eds.). Transformations of Kinship. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 214–243. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2019.

- Malinowski, Bronislaw (1929). The Sexual Life of Savages in Northward Western Melanesia. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Read, Dwight West. (2001). "Formal analysis of kinship terminologies and its human relationship to what constitutes kinship". Anthropological Theory. i (two): 239–267. CiteSeerX10.1.i.169.2462. doi:10.1177/14634990122228719. Archived from the original on 2013-01-eleven.

- Simpson, Bob (1994). "Bringing the 'Unclear' Family Into Focus: Divorce and Re-Marriage in Contemporary Britain". Human being. 29 (4): 831–851. doi:x.2307/3033971. JSTOR 3033971.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2008). Lewis Henry Morgan and the Invention of Kinship, New Edition. ISBN978-0-520-06457-7.

- Trautmann, Thomas R.; Whiteley, Peter Chiliad. (2012). Crow-Omaha : new light on a archetype trouble of kinship analysis. Tucson: University of Arizona Printing. ISBN978-0-8165-0790-0.

- Wallace, Anthony F.; Atkins, John (1960). "The Pregnant of Kinship Terms". American Anthropologist. 62 (one): 58–80. doi:10.1525/aa.1960.62.1.02a00040.

- White, Douglas R.; Johansen, Ulla C. (2005). Network Analysis and Ethnographic Problems: Process Models of a Turkish Nomad Clan. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN978-0-7391-1892-4. Archived from the original on 2013-x-05. Retrieved 2008-02-09 .

External links [edit]

| | Look upwardly kinship in Wiktionary, the costless dictionary. |

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kinship. |

- Introduction into the study of kinship AusAnthrop: inquiry, resources and documentation

- The Nature of Kinship: An Introduction to Descent Systems and Family System Dennis O'Neil, Palomar College, San Marcos, CA.

- Kinship and Social Organisation: An Interactive Tutorial Brian Schwimmer, University of Manitoba.

- Degrees of Kinship According to Anglo-Saxon Civil Constabulary – Useful Nautical chart (Kurt R. Nilson, Esq. : heirbase.com)

- Cosmic Encyclopedia "Duties of Relatives"

ingramtheyearect1981.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinship

0 Response to "Kinship Is Not Limited to Blood and Can Be Chosen Outside of the Family."

Postar um comentário